Games I Love: Beyond Good and Evil

In which I tell a little story about my experience with Beyond Good and Evil and the ways in which it impacted me as a game designer.

I was living in Japan when Beyond Good and Evil was released in US.

As such, I wasn’t able to secure a copy of it myself. If I’m honest, I can’t say I recall being aware of the game at the time. I’m sure I must have seen some media on it, but it certainly wasn’t on my list of must-have games. I bought it – or rather, I had a friend back in Michigan buy it for me – along with The Sands of Time because I saw a post on Evil Avatar that said their prices had been slashed to $20 within a week or two of release.

Looking back, it’s clear to me that this was one of the best gaming deals I’ve ever gotten. Perhaps, for reasons that will become clear later, it was the best deal of any kind.

I’m further ashamed to say that I didn’t play the game for quite some time. I couldn’t afford to have my friend actually ship the games to me, and in any case I was pretty busy just being in Japan. I finally got around to playing Beyond Good and Evil during Michigan Tech’s spring break of 2005. I had decided to stay in Houghton for the break to save on gas money and take care of some outstanding assignments, and as a result I had the apartment to myself (I lived with two other guys.) In exact accordance with expectations, I didn’t actually do much in the way of work and spent most of the time cranking through my backlog of games.

Beyond Good and Evil was the first one on the list.

It’s hard to say when, exactly, I first started to suspect that what I was playing was fundamentally different than the games I was used to. On the surface there isn’t anything particularly unique about what Beyond Good and Evil does: it’s Zelda with a different coat of paint. The combat system, though it flows well enough, isn’t very deep. There are stealth sections, but none of them do anything that hasn’t already been done better in other games. The photography angle is pretty unusual but it’s not the first game to have you take pictures of stuff.

Instead, what I think pushes Beyond Good and Evil past its contemporaries is Jade.

Good Characters Start With Firm Foundations

In the world of gaming, Jade is an enigma: a competent, strong, resourceful female lead that retains historically feminine elements like compassion and empathy. More than just a man with boobs, Jade’s character manages to present this without feeling heavy handed or clichéd. Like many game characters she doesn’t begin as a hero, but unlike most the critical aspects of her story are right there to see: she’s a freelance photographer who lives in a lighthouse and provides shelter for the orphaned children created by the war on Hillys. And this information isn’t presented simply for background – Jade’s devotion to the children is a core aspect of her personality, right from the opening attack and through the following sequences that let you explore the lighthouse and interact with the kids.

In that first 10 minutes we’re also treated to two emotional extremes – Jade the fighter, who doesn’t hesitate to risk her life in the protection of others; and Jade the vulnerable, injured and pessimistic but willing to lean on the support of her surrogate family. How many games manage to achieve this kind of character depth across their entire story, let alone in the opening sequence? For that matter, how many other games have had heroes whose defining qualities are empathy and caretaker instincts?

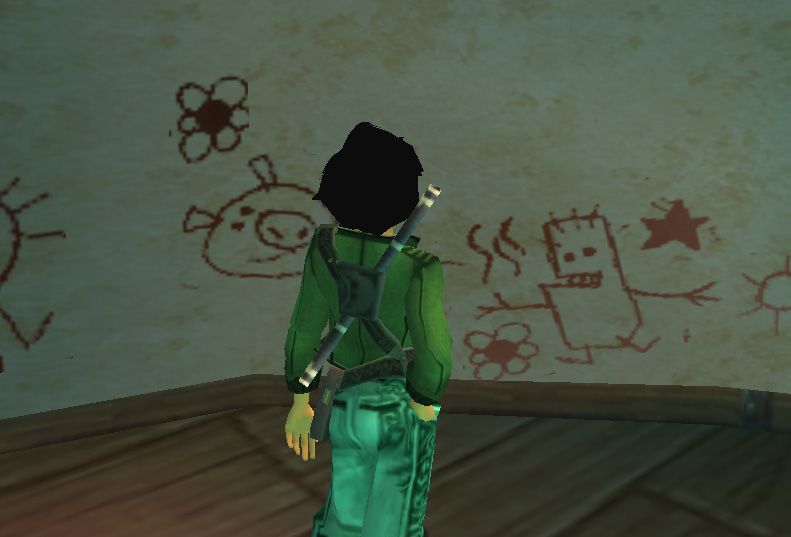

What’s more, most of this is done via the “show, don’t tell” philosophy also found at the core of Valve titles like Half-Life. We don’t learn this information by having it repeated to us via audio logs or presented as exposition. Most of it shows up simply via observing the way the characters act and the things you can find in the world: Jade’s room, full of drying photo prints of the kids and her uncle Pey’j; the lighthouse itself, full of crayon drawings on walls and other signs of the orphan's presence; her fearlessness in the face of the DomZ attack; the fact that the group’s income source is Jade Reporting, a business she started herself.

Even her choice of clothing conveys meaningful information. A sense of utility combined with style that isn't ashamed of her womanly assets but also doesn’t go out of its way to promote them. It’s the kind of outfit one could actually imagine seeing on a young female photographer/martial artist.

I could write at length about how alive the world of Hillys feels, and how watching the progression of resistance within the city (general agitation, graffiti, eventual full-on protests) from behind the mask of Shauni (Jade’s IRIS Network codename) makes for a very interesting experience: you’re the hero, but nobody really knows it. That’s a theme that’s been explored in a lot of other mediums and even a few other games.

Instead, the defining feature of Beyond Good and Evil’s open world was, for me, the moment of the second attack on the lighthouse. The timing of that sequence was not only the most brilliant moment of that gaming generation – it was also the first time I felt like I understood how games could tell a story in a way that was genuinely different from all the mediums that preceded it.

Your Choices Have Consequences

When we talk about modern game storytelling, the element that gets most commonly thrown around is player choice. As designers, we’re always trying to think of ways to give players a legitimate sense that their decisions have an impact in the world. The way most games try to solve this is through simplistic branching trees: you make a decision, and certain paths open while others close. Characters you meet will react differently depending on the sorts of paths you choose, and the differences between them are generally fairly clear (to the point of exaggeration, in many cases.)

Because the world of Hillys is open, you can decide to head on back to the lighthouse any time you wish.

The problem with this is twofold. First, making all of that additional content is really expensive. In an industry as ruthlessly competitive as ours, the notion of making a game where the typical player might never see a significant percentage of your content is pretty hard to sell to a publisher – there’s a reason why massive, western-style RPGs remain the domain of a few proven studios with rabid fan followings. Second, branching storylines are rarely, if ever, complex enough to satisfy the critics. No matter what you do, it’s virtually impossible to make a branching storyline that approaches even the most basic decision that a person makes every day in the course of normal life. This is a pretty significant problem when the primary purpose of your product is to entertain people with larger than life experiences, and it’s the reason why people like Chris Crawford have given up on games entirely and moved in an different direction.

Beyond Good and Evil gets around this problem in one of those ways that feels obvious as soon as someone points it out: it doesn’t actually give you a clearly defined point of decision.

Because the world of Hillys is open, you can decide to head on back to the lighthouse anytime you wish. For the first half of the game or so, the natural progression of the storyline takes you back there pretty regularly. Whenever I went back I made it a point to chat up the orphans because they often had interesting things to say about how events were proceeding. They had their own take on what Jade was doing and, in some cases, were slightly mysterious characters in and of themselves.

Around the time of the Nutripillis Factory mission, however, that changes. Once Jade gets deeply involved with the IRIS network their headquarters in the city becomes your central mission hub, and as a result there’s no specific game requirement for you to visit the lighthouse anymore. Around this time the missions also start to get longer, and you’re traveling to the farther reaches of the map to accomplish them. In between missions there are Alpha Section warehouses to raid, animals to photograph, races to win, smugglers to chase and the increasing effects of your actions to observe: the citizenry is getting more and more riled, and it’s fun to bask in the secret glow of your success and the irony of NPCs who think you haven't heard about Shauni's latest exploit.

Arriving at the island to find all of the children gone and the lighthouse itself in ruins was one of the most painful moments I’ve ever had in a game.

The Slaughterhouse mission, in particular, is quite long and has a number of emotional moments, but even with those the overall feeling is one of triumph. Your investigative photography is cracking the abuses of the Alpha Section wide-open and you can feel yourself progressing toward the inevitable showdown. As you finish that mission, you’re finally given a reason to return to the lighthouse to find the Beluga, a spaceship Pey’j was working on in secret. So excited was I to try out this new toy that I ran in and out without really talking to anybody and headed to the upgrade shop to purchase the space engine that it needed.

It’s after you purchase that engine, however, that the second lighthouse attack occurs.

I never had a choice in this. The Alpha Section was going to attack and destroy the lighthouse when I bought that space engine regardless of what I did or didn’t do over the course of the game – it was a scripted moment and it will play out the same way no matter how many times you play the game. But at that moment, when I exited the shop and saw the explosions, saw the foreboding pillar of smoke, and heard Jade’s frantic exclamations confirming what I could already see, that fact never occurred to me.

As I raced back to the lighthouse as fast as the hovercraft’s booster items could make it go, all I could think about was how long it had been since I’d really been there.

I could have gone back to that lighthouse at any moment, but I didn’t. It certainly wasn’t going anywhere…right?

Arriving at the island to find all of the children gone and the lighthouse itself in ruins was one of the most painful moments I’ve ever had in a game. There was a deep, profound sense that what had happened was my fault. That I (and by extension, Jade) had become so wrapped up in my adventures and the broader mission to save Hillys that I had completely forgotten what got me started: the desire to protect those kids. I wondered what I might have missed, what interesting story tidbits the kids might have had to say that I’d missed because I couldn’t be bothered to go back home.

The scene that follows is heartbreaking, with Jade defeated and despondent over the loss of the kids. You can see the guilt on her: she knows that this is her fault, and her feelings closely mirror what the player is feeling in that moment. Never mind that this was a scripted event that couldn’t have been prevented; in the moment, there’s no thought of that. There’s only a shared emotional connection between what happened on the screen, what the character is feeling, and what the player is feeling.

Of course, this sort of thing is perfectly mechanical, and other mediums have been executing this framework in varying ways for centuries. Every good story needs its low point, when everything has fallen apart and there seems to be no hope of proceeding. The difference here was that I wasn’t just mirroring the emotions of the protagonist, but instead genuinely sharing aspects of her grief.

I could have gone back to that lighthouse at any moment, but I didn’t. It certainly wasn’t going anywhere…right?

The Personal Experience Is What Matters

I’ve never been certain whether or not the buildup to that scene was intentional on the part of Ancel and the other designers. Certainly the scene was meant to be emotional, and even without the buildup it’s one of the more effective low points in any game. But did they specifically design the missions to keep you away from the lighthouse? Did they make a conscious decision to make sure that the most interesting things to do were in the city, or on the outskirts of Hillys, instead of at the lighthouse?

In other words, were they trying to steer me away from Jade’s home to deepen the impact of that scene?

I’ve never seen Ancel write anything on that subject, and in fact I’ve never seen the question asked in an interview. Short of having the opportunity to ask him myself I’m not sure the question will ever be answered. Certainly, I'm not the only one who found that scene especially heart wrenching!

But therein lies the critical takeaway from Beyond Good and Evil: in the end, designer intent doesn’t really matter. What’s important is what the individual player takes away from the experience, and what our medium can do to enhance those feelings. We don’t have to engineer choices into our games, with a flow chart indicating how each one will affect the player’s alignment, mission choices, NPC reactions, whatever. If you give the players the ability to make a decision as simple as where to go at any given moment, you’ve already created the potential for emotional impact far surpassing what’s achievable in a static medium like movies or literature. The ability to have a truly individual experience is one area where games have the clear upper hand.

In the end, Beyond Good and Evil is important to me not just because of my memories of the game itself, but because it’s one of the two games that convinced me to pursue game design as a career. Up until then I’d been a gamer for a long time, and had been interested in the critical aspects of games for quite a while, but I hadn’t entertained the idea that creating them was something I wanted to do.

After that second lighthouse attack in Beyond Good and Evil, it was hard to imagine wanting to do anything else.

This post is part of a series of articles on the games that have shaped me as a designer. They tend to be long, focus less on hardcore design analysis and are honestly closer to love letters than anything else. It probably goes without saying, but each of these articles will be full of spoilers. For other posts in this series, check out Games I Love.